Thesis Summary

1) Abstract:

The thesis notes the interactions of informal institutions moderated by formal institutions under the guise of property rights(PRs) and access to finance (ATF) examining its association with Total Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA). The thesis examines these interactions in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. This group is an intergovernmental economic organisation with 37 member countries, founded in 1961 to stimulate economic progress and world trade. The thesis studies the time-period of 2010-2020 using an unbalanced data panel multivariable regression analysis consisting of 32 countries using a fixed-effects model. This is done due to exogenous shocks influencing formal institutions from events like the financial crisis aftermath, Brexit, the 2016 U.S. election and the Covid-19 pandemic. This time period is significant as the shocks generated by the events mentioned above will have had significant influences on formal institutions influencing their moderating effects on TEA.

2) Thesis Background:

The origins of entrepreneurship in the 20th century came about under the work of Max Weber. Weber’s research into how entrepreneurship had historically facilitated economic development led to early foundations of entrepreneurship. Contemporary research around entrepreneurship can be seen to have occurred after the Second World War (around 1949) (Cuervo, Riberio and Roig, 2007). The peak point of interest in this field came about in 1979 with the Birch Report which was titled ‘‘The Job Generation Process’’ (Gupta, 2020). This report highlighted that the period of 1969-1976 exhibited 50% of employment created in the United States (U.S.) coming from new start-ups. These statistics attracted the interest of policy makers in government as well as the academic community (Cuervo et al., 2007).

Figure 1: Share of employment created by the birth of enterprises in 2016 for individual countries. Source: OECD (2018).

On average, OECD countries’ start-up firms account for about 20% of employment but create almost half of all new jobs (OECD, 2018). The impact of entrepreneurship rates is seen in Figure 1(above). Figure 1 illustrates the share of employment growth occurring in the OECD countries. This demonstrates the reason why local governments and policy makers pay attention to entrepreneurial activity. The service sector continues to be the largest source of employment created by enterprise formation in countries. Across countries, the highest job creation rates were seen in leisure-based activities (e.g. entertainment), professional, scientific, and technical activities, and real estate. These industries are responsible for, in some cases, as much as 16% of the total employment in their countries (OECD, 2018).

The thesis will analyse entrepreneurship via the lens of Neo-institutional Theory (NIT). Institutional theory examines interactions between set groups and organizations who attempt to secure their positions in society through legitimacy (Scott, 2008). Organisations must conform to the rules and norms within an institutional environment (Scott, 2008). Bruton, Ahlstrom and Li (2010) comment that an advantage of utilising this perspective lies with the incomplete picture presented by entrepreneurship theories which ignore social elements of entrepreneurial activity (Barley and Tolbert, 1997). NIT was introduced in 1977 by Meyer and Rowan (1977) (Alvesson and Spicer, 2019). There are three pillars that NIT possesses.

The regulative pillar emphasizes the ability to set rules (formal) and establish rewards or punishments that influence future actions (Scott, 1995). Regulations are seen to have a mixed impact on TEA. Valdez and Richardson (2013) highlight small-medium size enterprises (SMEs) (compared to larger firms) are disproportionately affected by administrative costs associated with government regulations. However, McMullen, Bagby, and Palich, (2008) demonstrate that regulative institutions are related to the levels of TEA where the dimensions are understood to affect different types of entrepreneurship differently depending on the Gross Domestic Product per capita (GDP p/c) of a country.

Next, the normative pillar provides a degree of stabilisation on an individual in society where individuals strive to act in a socially acceptable manner (Scott, 1995; March and Olsen, 1989).

Cultural-cognitive component refers to the collective understandings of social reality, the framing of meaning within a society (including national and individual levels of analysis). This states that cognitive contexts contribute to the formation of individual interpretations and beliefs (Scott, 1995).

From these three pillars, categorisation of the institutions are broken into two. Informal institutions influence TEA through looking at norms (normative pillar), values and culture (cultural-cognitive pillar) (e.g. Hasan, Kobeissi, Wang and Zhou, 2017; Stephan, Uhlaner, and Stride, 2015). Linan and Fernández-Serrano (2014) and Hechavarria and Reynolds (2009) show that culture is a significant factor in predicting TEA at the country level. A prevalent discussion surround whether national culture and informal institutions are equivocal. The author adopts the approach of Alesina and Guiliano (2015) where national culture and informal institutions are synonymous. They prefer the term culture over informal institutions as it is seen as more appropriate because informal institutions would imply that formal institutions determine informal ones. National culture dimensions themselves have shown to have an influence on TEA. Dimensions like individualism (IND), Power Distance (PD) and Uncertainty Avoidance (UA) all have copious amounts of research showing their impact on TEA (e.g. Nikolaev Boudreaux and Palich, 2018; Stephan and Uhlaner, 2010; Zhao, Li and Rauch, 2012; Autio, Pathak and Wennberg, 2013; Wennekers, Thurik and Van Stel, 2007; Verheul, Wennekers, Audretsch and Thurik, 2002).

The regulative pillar concerns formal institutions (FIs). FIs are the written, formally accepted rules which have been implemented to make up the economic (and legal) infrastructure of a given country (Tonoyan et al., 2010). These are thought to influence TEA in many ways, ranging from improving the rule of law, safeguarding innovators and their intellectual property (e.g., Acemoglu and Robinson, 2012; Autio and Acs, 2010). The formal institutions this thesis examines are PRs and ATF.

PRs (The Heritage Foundation, 2021) are laws examining the ability of individuals to accumulate property, these are secured and fully enforced by the state. Institutions establish the conditions in which TEA will be developed. Formal institutions are argued to have a moderating effect on TEA. Angulo-Guerrero, Pérez-Moreno and Abad-Guerrero (2017) understand that an institutional environment providing a high-quality legal system and protection of PRs tends to facilitate innovations and risk-taking moderating the influence of informal institutions adequately resulting in opportunities for entrepreneurship (Bjørnskov and Foss, 2013).

ATF is crucial for entrepreneurship (Cassar, 2004), as additional funding allows entrepreneurs to sustain or grow their ventures. Prior research highlights that the lack of ATF encountered by entrepreneurs is commonly explained to be the biggest constraint to the creation and development of ventures (e.g. Omri, Ayda-Frikha and Bouraoui, 2015). Transaction cost economics (TCE) suggests that when the costs of TEA is high, entrepreneurs may obtain cheaper financing through alternate means (Williamson, 1988; Aggrawal and Zhao, 2009). Such alternatives may be entrepreneurs utilising their own savings or getting loans from family (or friends). ATF is likely to improve the quality of entrepreneurship through channelling the ventures into more productive activities (Sobel, 2008).

However, the absence of regulatory enforcement can also positively affect the presence of TEA. The absence of banking regulations has enabled a comparative growth of financial technology (FinTech) start-ups in countries without a major financial centre (Block, Colombo, Cumming and Vismara, 2018).

The ‘Strict Hierarchy of Institutions’ hypothesis (Davis and Williamson, 2016) points to the nature of interactions between both institutions. Informal institutions interact proportionally with formal institutions on their influence on policy. Brinekrink and Rondi (2021) argue that the extent to which firms rely on innovation-stimulating motivations are ultimately created by more than just strong formal institutions. It is likely reliant on the configuration of informal institutions (Filatotchev, Chahine and Bruton, 2018) and collective understandings in the environment alongside the formal institutions.

The question is raised on the importance given to whether informal institutions are independent or part of formal institutions. Williamson (2000) highlights the various levels of institutions present in his framework. This framework is demonstrated in Figure 2 (below). On the lowest level (L4) resources are allocated through market exchange. Economic activity is performed via the price mechanism and economic actors ‘bidding’ for resources (Williamson, 1985). In L3, governance structures fix relative prices to capitalise on frictional costs in the market that obstruct efficient resource allocation (Williamson, 1996). Actions taken in L3 and L4 generally constitute what is known as ‘the market’. L2 constitutes the FI framework (‘rules of the game’), how the economy functions (North, 1990). The institutional purpose of this level is primarily to define and secure PRs (Bylund and McCaffrey, 2017). This also regulates economic action via policy action. Finally, L1 encompasses and embeds the lower institutional levels in an even broader setting of cultural values and norms that are not the subject of narrow economising. Each level includes specific institutions that constrain specific actions on lower levels (Bylund and McCaffrey, 2017).

Figure 2: Level of economics of institutions. Source: Bylund and McCaffrey, 2017.

3) Literature Gap:

A literature gap is discovered in two areas. The first one is expressed by Sun, Shi, Ahlstrom and Tian (2020) who comment that work is to be done on how formal institutions moderate and positively influence entrepreneurship through a variety of mechanisms. Entrepreneurship research can bridge the gap on the institutional influences of entrepreneurship and development (Ács and Storey, 2004). Bruton et al. (2010) stress that there is almost a singular focus on culture in institutional theory studies. Bruton et al. (2010: P.432) conclude that the effect of specific cultural dimensions on development after controlling for economic system, is inconsistent. This suggests that strong moderators such as specific institutional measures could help solve this confusion.

Additionally, the literature gap also focuses on the long-term orientation (LTO) and the indulgence-restraint (IVR) dimension of informal institutions alongside formal institutions under the guise of PRs and ATF. LTO refers to the extent to which a culture emphasises delayed gratification on material, social, and emotional needs (Hofstede, 2001). Buck, Liu and Ott (2010) understand that LTO (also known as Confucian dynamism) is probably the most important cultural dimension via its association with a nation's propensity to save, invest, and thus its per capita income growth potential. Wood, Bakker and Fisher (2021) comment that an entrepreneur’s conception of time significantly impacts on their activities. They understand that entrepreneurs across industries universally emphasise the importance of time in their actions as critical to the effectiveness of their activities.

The IVR dimension relates to immediate gratification versus deferment of basic human desires related to enjoying life (Hofstede, 2011). Empirical evidence also suggests that high IVR positively correlates with country level innovation performance (Lažnjak, 2011). Innovation, in turn, may be conducive to the translation of intentions into actions affecting TEA. Boubakri, Chkir, Saadi and Zhu (2021) find that individuals in high IVR countries are generally optimistic and encourage debate in the decision-making processes.

LTO is lacking in-depth studies which examine LTO as a main effect variable on a country’s economy (national level). Kirkman, Lowe and Gibson (2006) investigate studies examining the different levels of analysis conducted for each informal institution dimension. It is noted that only two papers have examined LTO at a country level and none at the group/organisational level, and that no studies examine LTO in a moderating context at the country level either. This is seen in Figure 3 (below, see 'Confucian dynamism'). Further examination of these dimensions is conducted by Kirkman, Lowe and Gibson in 2017, but LTO (at a country level) is still absent. No information is present on the IVR dimension since it is a relatively new dimension. Some literature analyses LTO and its impact on family firms (e.g. Fu, 2020) but this is lacking overall. Hechavarrıa, Matthews and Reynolds (2016) emphasise that new (nascent) entrepreneurs take about 46 months to establish a venture, which suggests an LTO dimensions perspective. Bogatyreva, Edelman, Manolova, Osiyevskyy and Shirokova (2019) propose that involvement in TEA presumes high risks that usually take substantial time to be realised.

Figure 3: Number of inclusions of cultural values by type of effect and level of analysis. Source: Kirkman et al. (2006).

Therefore, the research question posed is: ‘‘How do informal institutions moderated by two FIs (PRs and ATF) influence levels of TEA at a country level?".

4) Intended Contribution to Knowledge:

Having set out the literature, literature gap, research question, the intended contributions of this thesis are threefold: The first is the LTO dimension. Given that there are studies of LTO on entrepreneurship, this thesis is designed to fill that gap. Next, the indulgence (IVR) informal institution dimension and its effect on TEA has been neglected. This relates to the degree of gratification versus control of basic human desires related to enjoying life (Hofstede, 2011). Indulgence stands for a tendency to allow free gratification of basic and natural human desires. The other side, restraint reflects that gratification needs to be curbed and regulated via strict social norms. Given this is the latest informal institution dimension (Hofstede, 2011), this thesis will attempt to fill a literature gap looking at this dimension as a main effect on TEA. Finally, interactions between informal institutions and formal institutions (with formal institutions moderating the effect of informal institutions’ impact on TEA) in institutional theory is addressed. Research examining how institutions moderate and positively influence entrepreneurship through a variety of mechanisms is ultimately required (Sun et al., 2020).

5) Significance of Research:

An argument presented is that formal institutions (regulative component of NIT) is usually the main determinant of TEA in a country. Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson (2001) attribute economic success to the type of legal institutions designed by the colonizing power. If formal institutions were the sole factor in generating TEA, copying the U.S. constitution would allow countries to be economically successful (Guiso, Sapienza and Zingales, 2015). This was tried unsuccessfully in Latin American countries. Social norms are needed to sustain formal norms. When laws conflict with norms, compliance of regulations are weaker (Acemoglu and Jackson, 2015). This is why importance should not be solely given to formal institutions but with interactions of both institutions.

6) Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses:

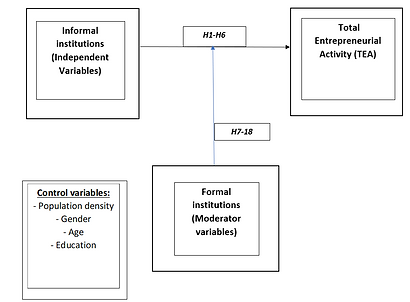

Figure 4 (below) outlines the theoretical framework, with links between formal and informal institutions and TEA. The various hypotheses are stated, with justifications for their rationale briefly explained. These are categorised into 3 groups.

Figure 4: Theoretical Framework. Source: Author.

The first group looks informal institutions and their direct association with TEA. In the literature, PD is understood to be mainly negatively related to entrepreneurship (Hechavarría and Brieger, 2020; Dubina and Ramos, 2016; Autio et al., 2013). Hechavarría and Brieger (2020) understand that societies high in PD view power as a mechanism to maintain social order. Such societies are structured via social classes that differentiate groups and restrict upward social mobility.

H1: PD is negatively associated with TEA.

High levels of IND (individualism) are likely to be positively associated with TEA, as entrepreneurs will be oriented towards self-interest, autonomy, and risk- taking which may translate into rewards for entrepreneurs. High IND countries may tend to be more oriented towards the achievement of personal goals (Dubina and Ramos, 2016; Kirkley, 2016). IND is positively related to TEA in empirical studies (Nikolaev et al. 2018; Stephan and Uhlaner 2010) and to innovation (Bennett and Nikolaev, 2020; Rinne, Steel and Fairweather, 2012).

H2: IND is positively associated with TEA.

High MAS (masculinity) levels imply traits like assertiveness, competitiveness, and measurable accomplishment positively related to TEA (Kirkley,2016). It is assumed that high MAS (i.e., material success-oriented values) is likely to be positively associated with motivations for starting a new venture. Similarly, in low MAS societies, the emphasis may be on relationships and a friendly atmosphere (Dubina and Ramos, 2016).

H3: MAS is positively associated with TEA.

Low levels of UA (uncertainty avoidance) in a country may encourage entrepreneurial entry because values such as openness to ideas and extraversion are prominent (Bräandstatter, 2011; Thomas and Mueller, 2000). Individuals who are more comfortable with uncertainty and ambiguity can appropriate a first-move rent via establishing a venture (Falck, Heblich and Luedemann, 2012). The process of establishing a venture starts with high levels of UA, this is because of a lack of precedence for the entrepreneurs for setting up a venture (arising from uncertainty).

H4: UA is negatively associated with TEA.

LTO (long-term orientation) values include perseverance and favour high risk ventures that generally take time to be realised. Bogatyvera et al. (2019) conclude that high LTO produces more pragmatic attitudes and is believed to have a positive impact on entrepreneurial cognition. The foundation of a firm takes on average 46 months to be realised (Bogatyvera et al., 2019), already beyond the short-term. A culture characterised by lower LTO may push people to choose employment with a stable and transparent salary option. They may not promote their entrepreneurial intentions unless the rewards are high and quick, which may be rare with ventures (Bogatyvera et al., 2019).

H5: LTO is positively associated with TEA.

The indulgence versus restraint (IVR) dimension relates to the gratification versus deferment of basic human desires with regards to enjoying life (Hofstede,2011). Countries with high levels of IVR (indulgence) emphasise the individual's happiness (Guo et al., 2018). High IVR levels increase the likelihood that individuals will leave their workplace if they are not satisfied, implying low restraint (MacLachlan, 2013), causing them to pursue their own ventures. This increases the chance of an individual moving from intention into action (Carter et al., 2003).

H6: IVR is positively associated with TEA.

The second group looks informal institutions moderated by PRs and its association with TEA. H1 proposes a negative association between PD and EA. Fang, Lerner and Wu (2017) emphasise that recent evidence has shown that strong PR protection can encourage entities to more confidently engage in innovation- based TEA (e.g., Cohen, Gurun, and Kominers, 2019). In high PD societies, access to resources may be constrained to high power groups.

H7: Effective PRs will positively moderate the negative association between PD and TEA.

H2 proposes a positive association between IND and TEA. The effect of IND is seen to be positively moderated by the quality of formal institutions that further support TEA (Gantenbein, Kind and Volonté, 2019). Higher levels of IND may also be associated with conditions that favour TEA. Zhang, Liang and Sun (2013) show that IND is related to investment protection (PR), entrepreneurs will want to protect their property and will be concerned with the rewards (e.g., potential profits, status) associated with their TEA. This may further increase the willingness of financial institutions to provide funding for TEA.

H8: Effective PRs will positively moderate the positive association between IND and TEA.

H3 asserts that MAS is positively associated with TEA. There is not enough empirical evidence to be decisive on the expected moderating influence of PR on the relationship between MAS and TEA (Boubakri et al., 2021). Aidis, Estrin and Mickiewicz (2007) claim that countries with tight protection of PRs show better results in terms of innovation. Since MAS is associated with creativeness and innovation (Simón-Moya, Taboada and Fernández-Guerrero, 2014), strong PRs may support MAS facilitating innovation, thus stimulating TEA.

H9: Effective PRs will positively moderate the positive association between MAS and TEA.

H4 proposes that high UA be positively associated with TEA. In addition, effective PR protection may encourage TEA in high-UA societies. Entrepreneurs may be uncertain about whether the state will protect private PRs for their venture in high UA countries (Alvarez and Barney, 2020). Therefore, effective PRs may reduce uncertainty quicker for entrepreneurs. Sjaastad and Bromley (2000) insist that the concept of security and the assurance element in PR is a necessary element for TEA, implying that PRs ultimately reduce uncertainty for entrepreneurs.

H10: Effective PRs will positively moderate the negative relationship between UA and TEA.

H5 proposes that LTO may be positively associated with TEA. Inadequate PRs imply institutional constraints may negatively impact TEA by affecting an entrepreneur’s ability to understand the current and future institutional environment. This raises questions regarding enforcement of the ‘rules of the game’(North, 1990). Wood et al. (2021) explain that once resources are utilised for establishing a venture, they are difficult to recuperate. Lortie, Barreto and Cox (2019) conclude that the protection of PRs encourages companies to make future-oriented investments regarding the venture’s performance, as there is more certainty that they can protect and benefit from the returns to these investments. The effectiveness of PRs help reduce uncertainty in ventures by guaranteeing a set of long-term contractual obligations.

H11: Effective PRs will positively the positive association between LTO and TEA.

H6 proposes that high IVR be positively associated with TEA. High levels of IVR give more freedom for individuals to satisfy their desires (Hofstede et al., 2010). Effective PR may allow the desires of entrepreneurs to be realised, providing some level of certainty during the process of nascent entrepreneurship.

H12: Effective PRs will positively moderate the positive association between IVR and TEA.

The last group looks informal institutions moderated by ATF and its association with TEA. H1 proposes that low PD be positively associated with TEA. Prior literature suggests that in high PD countries, ATF is governed by dominant groups and nascent entrepreneurs may not be able to access financial resources (Malul and Shoham, 2008).

H13: Easier ATF will positively moderate the negative association between PD and TEA.

H2 proposes that IND be positively associated with TEA. IND fosters entrepreneurial attitudes as it may be a proxy for decentralised, pro-market attitudes (Ang, 2015). This would mean entrepreneurs would be more willing to use ATF positively affecting TEA. IND is associated with competitive market-based systems that provide financing to innovative and growing firms (Boubakri and Saffar, 2016). This points to a more decentralised ATF system that may reinforce the effects of IND as individualistic entrepreneurs may approach managers of small finance providers.

H14: Easier ATF will positively moderate the positive association between IND and TEA.

H3 predicts that high MAS may be positively associated with TEA. In high MAS societies, entrepreneurs are more likely to engage in TEA (Khan,Gu, Khan and Meyer, 2021). This might increase competition and is widely recognized as stimulating the scale and efficiency of as well as ATF (Khan et al., 2021). Additionally, managers in high MAS countries tend to encourage bank lending and leverage increasing ATF impacting TEA positively (Haq, Du, Saff and Pathan, 2018).

H15: Easier ATF will positively moderate the positive association between MAS and TEA.

H4 proposes that low UA may be positively associated with TEA. Li and Zahra (2012) analyse the decisions of venture capitalists wanting to invest in new ventures, they are less responsive to the incentives offered by formal institutions in countries with higher UA levels. In the context of high UA, financial return is not the primary goal (Di Pietro and Butticè, 2020). If ATF is uncertain, TEA will be reduced in high UA societies.

H16: Easier ATF will positively moderate the negative association between UA and TEA.

H5 proposes that LTO may be positively associated with TEA. Zhao and Jones-Evans (2017) explain that to achieve high TEA, investments made by growth-oriented ventures require long-term financing. It may take substantial time for entrepreneurs to transform investments into stable cash flows. Overdrafts from financial institutions are repayable on demand while loans are usually less than 10 years. Loan repayments must be made on a regular (short-term) basis which requires stable income for entrepreneurs (Zhao and Jones-Evans, 2017).

H17: Easier ATF will positively moderate the positive association between LTO and TEA.

H6 suggests that high IVR may be positively associated with TEA. Currently, there is a lack of literature available on this relationship. High IVR positively correlates with country level innovation (Hofstede et al., 2010). Therefore, greater ATF (alongside the benefits of expertise) should aid TEA by allowing prospective entrepreneurs to engage in their happiness in high IVR societies but who may not have the financial means necessary to do so. ATF will therefore facilitate a positive moderation of TEA.

H18: Easier ATF will positively moderate the positive association between IVR and TEA.

7) Research Philosophy and setting:

The author approaches the positivist paradigm in the thesis. A structured approached is required where a precise research question and hypotheses are formed. Social agency is considered a physical object that may be observed and the interactions that occur as considered a natural occurrence (Zyphur and Cieredes, 2020). Positivism adopts a stance where facts are quantifiable and causal explanations amongst explanatory variables exist (Saunders et al., 2019). Statistical analysis techniques may be applied in positivist research to obtain quantifiable and objective results that can be context and time-still knowledge (McLaren and Durepos, 2021).

Following a positivist stance as explained above, this research will use a deductive approach. Flick (2018) comments that when examining the relationship between theory and data, the process to discover and/or verify new patterns or ‘themes’ arises. Raw data is examined to see if the theory is supported (Reichertz, 2007). In this approach, variables are conceived in advance, and a research question/hypothesis is first formed (Trochim, Donnelly and Arora, 2006). However, the objective of a deductive approach setting is not to examine the theory per se but to adopt the theory as a ‘lens’ in which to examine and make sense of the data available to the researcher (Flick, 2018). The author follows this approach process in the thesis.

A justification from the literature is now needed. Kostova et al. (2020: P.468) summarise a 20-year literature review on NIT and its various pillars. They comment that “…introducing the institutional lens as an alternative to culture (Kostova, 1997)… provides a broader view of national contexts, encompassing not only cultural but also regulatory and cognitive elements (Kostova, 1997; Scott, 1995)… allows the capturing of the dynamic aspects of context... Theoretically, it can be more precise in its predictions than cultural distance if analysed with regard to a specific issue”. Such a citation illustrates that there are set pillars of NIT which have their own characteristics surrounding them providing a more holistic understanding of a phenomena. Kostova also refers to institutional theory as a ‘lens’ further reinforces this. The researcher adopts a deductive approach.

The study notes the influence of institutions on TEA of 32 OECD nations examining the period of 2010-2020. New Zealand (NZ), Israel and Costa Rica are excluded due to incomplete data points. In addition, the Latin American (L.America) countries (Chile, Colombia and Mexico) are removed because of the proportion of OME: NME ratio. This arises from extreme inequalities present in L.American countries. Matteos (2021) comments “…In terms of economic participation, there is a large difference between central regions and non-central regions”. Structural inequalities present in L.America generate a higher level of NME compared to the other OECD countries, and Matteos (2021) further comments that many other L. American countries (e.g., Mexico) have highly concentrated socio-economic areas.

A reason to focus on OECD nations is their proportion of world GDP and geographic spread. The OECD covers 5 continents. This geographic spread allows generalisability amongst the findings from this study. Only countries on the African continent are not represented. Further, the OECDs (2020) share in world GDP (expressed in Purchasing Power Parities (PPPs)) stabilises at approximately 50% between 2011 and 2017. The share of each country is summarised in Figure 5 (below). Figure 9 depicts that the USA has the largest of the OECD nations capturing 16.3% of world GDP.

Figure 5: Share of World GDP based on PPP by country for 2017. Source: OECD (2020).

There are a variety of studies that use OECD as a cross-country examination group with varying timeframes. Abdesselam, Bonnet, Renou-Maissant and Aubry (2018) examine 26 OECD countries (1999–2012), examining EA, growth and labour markets. Additionally, Angulo-Guerrero, Pérez-Moreno and Abad-Guerrero (2017) study 33 OECD countries and the relationship to economic freedom from 2001-2012. Their study examines OME and NME separately and examines 29 and 30 countries for both EA types. Wennekers et al. (2007) studies the relationship of UA and TEA across 21 OECD countries (1977–2004). The years are ‘pooled’ so that 3 years (1976, 1999 and 2004) are analysed to account for the stability of the direct relationship of variables in question over time. Further studies look at the relationship of income development levels (GDP p/c) and ownership rates (nascent or established entrepreneurship).

The period chosen for this study is 2010-2020. During this period, certain exogenous shocks occurred (e.g., recovery from the 2008 financial crisis, the UK leaving the EU, Covid-19) that impacted the way formal institutions function. In this setting, direct independent variables will be informal institutions as influences on entrepreneurs. Within our study period, some formal institutions have been disproportionately subjected to change.

8) Level of analysis of EA:

The thesis will deploy a macro-level of analysis. This is because of the stream of literature and measures deployed looking at both informal and formal institutions. For informal institutions, national culture (aggregate) measures of entrepreneurship will be used. Formal institutions will also be examined at a macro-level. Both categories of institutions will be examined in the upcoming sections in this Chapter.

Dacin, Goodstein and Scott (2002) understand institutional change can proceed from the most micro (interpersonal) levels to the most macro (national/global) levels. This level of analysis section is to make the reader aware that there are different levels to consider. These are summarised in Figure 6 (below). Institutional pressures operate at many levels (Fini, Fu, Mathisen, Rasmussen and Wright, 2017). These levels can be viewed as interacting within a nested structure, where each institutional level will have distinct influence on participation in entrepreneurship (Rasmussen, Mosey, and Wright, 2014). Figure 6 looks at work based on Hedström and Swedberg (1998). Causal mechanisms can be organized on multi-level categories, including i) situational mechanisms, ii) action-formation mechanisms, and iii) transformational mechanisms. Situational mechanisms describe the contextual and environmental influences on entrepreneurial opportunities, linking macro and meso to the micro-level. Action-formation mechanisms entail the processes of ventures (micro-level) as well as entire markets (meso-level). Finally, transformational mechanisms explain the collective effects of ventures (micro-level) on markets (meso-level) and institutional settings (macro-level) (Kim, Wennberg and Croidieu, 2016).

Figure 6: Multilevel causal mechanisms framework. Source: Kim et al. (2016).

Nearly all the existing research indicates a top-down entrepreneurial mechanisms from macro to micro-level mechanisms (ABC points in Figure 10). In such analyses, formal institutions have been most thoroughly studied because these are arguably the most regularly clarified in the literature (Williamson, 2000). They are easy to identify and measure across contexts and over time (Andersson and Henrekson, 2014).

Multi-level analyses remain rare in the entrepreneurship literature (Zahra and Wright, 2011). To deal with the constraints of the trait-based literature, the level of research is stretched to the national level (Valdez and Richardson, 2013).

However, care should be taken when using aggregated individual level data to explain macro-level outcomes. The use of individual-level perceptual data on social influences can lead to inherently weak multi-level analysis. This because the association between an individual’s perception of social influences and their actual behaviour is individual-specific and may not ‘average out’ when aggregated (Manski, 1990). Macro outcomes depend on both micro-level actions and their interactions. To overcome the issue of multi-level analysis a maximum-likelihood regression model is used (Bickel, 2007). Although, other regression models can be used so long as the errors belong to a normal distribution in a model. This one of the assumptions that must be fulfilled with a regression model. Bickel (2007) further stresses that multi-level models are essentially regression analysis where the observations are ‘nested' (grouped) into identifiable contexts. The thesis does this by looking at TEA within specific OECD countries.

9) Variables used in the thesis:

Dependent variable: GEM- TEA

The dependent variable is TEA, since 1997 one of the most prominent variables, the most well-known and cited measure from the GEM database within the entrepreneurship literature (Kiran and Goyal, 2021; Bosma et al., 2018; Dheer, 2017; De Clercq, Danis and Dakli, 2010). It considers the percentage of the adult population (18–64 years of age) within each nation that is either currently engaged in the process of creating a new business venture (nascent entrepreneurship) or are operating a venture that has paid salaries or other forms of payment for at least three months but no more than 42 months (early-stage entrepreneurship). This is contrasts with established entrepreneurship which is 43 months or more (GEM, 2021).

Not every nation is surveyed annually. For example, N.Z. has no data since 2005 (GEM, 2021). Such missing cells mean that, to maximise the sample of OECD nations, TEA data (as well as all other measures used in the thesis) have been imputed for the years of 2010-2020. Imputation refers to using the mean (average) of the values for specific data points where the data is missing or unusable (Newman, 2003). An average (imputed) TEA measure is created based on this data for each nation during the period.

Independent variable: National culture- Hofstede’s Index

The main independent variable that this thesis will use for the informal institutions index is called Hofstede’s Index. Hofstede was hired as a psychologist on the international staff of the multinational technology company IBM Europe (Sent and Kroese, 2020). The company wanted to preserve its strong market position; Hofstede was hired to observe the ways IBM personnel performed their tasks in different countries. From this the Hofstede national cultural index was invented. Hofstede conducted personnel surveys on employees with questions on matters like salary, working relations and employees' expectations of their managers. Between 1968 and 1972, standardised paper-and-pencil questionnaires were filled in by 117,000 employees in 72 countries in 20 languages.

National culture is seen as the set of shared values, beliefs, and expected behaviours (Hofstede, 1980). Initially, four dimensions were utilised in the index. These are UA, IND (low IND), PD and MAS (low MAS). Hofstede and Bond (1988) added the dimension LTO. This was included in his second book (entitled Cultures and Organisations: Software of the Mind) published in 1999. The final dimension IVR was added in 2010 with Minkov. Even though Hofstede's index is not without limitations (Baskerville, 2003) it represents a concise taxonomy of significant cultural dimensions for explaining the behavioural preferences of people in a society and continues to be widely used in entrepreneurship cross-cultural studies (e.g., Bogatyreva, Edelman, Manolova, Osiyevskyy, and Shirokova, 2019; Wennberg, Pathak and Autio, 2013). All six dimensions are scored out of 100, the higher the score means the higher the representation of the actual dimension within a nation.

Hofstede’s index is the most widely used model due to consistent research with similar dimensions in other indices and predictive of economic outcomes. Hofstede offers the most complete country coverage (Cox and Khan, 2017). Two major studies review research carried out with Hofstede’s variables; the first is Kirkman, Lowe and Gibson (2006) who review 180 published studies. Søndergaard (1994) further reviews 61 empirical studies. Both find overwhelming confirmation of Hofstede’s dimensions. The other large study by Beugelsdijk, Kostova and Roth (2017) state that Hofstede’s work has come to dominate the literature, partly because he was the first to develop a concise national culture framework consisting of multiple national cultural dimensions.

Moderating variables: Formal Institutions (FIs)- IEF

The next index represents the FIs in this thesis as moderators. Both components PRs and ATF are dimensions of FIs. To recap, FIs are institutions (e.g., regulations) which comprise a part of the tangible rules that guide behaviour to make sense of a situation (North, 1990). The IEF (Index of Economic Freedom) began in 1995, this is published by The Heritage Foundation (a Washington think tank) and the Wall Street Journal (IEF, 2021). IEF measures economic freedom (EF) based on 12 quantitative and qualitative dimensions grouped into four broad categories of EF:

i) Rule of Law: Involves PRs, government integrity and judicial effectiveness

ii) Government Size: Consists of government spending, tax burden and fiscal health

iii) Regulatory Efficiency: Covers business freedom, labour freedom and monetary freedom

iv) Open Markets: Entails trade freedom, investment freedom and financial freedom (ATF)

A country’s overall score is derived by averaging these 12 components, with equal weight being given to each (IEF, 2021). For the following reasons below, this thesis examines two FIs represented in the IEF index (PRs and ATF).

PRs determine the ability of individuals to accumulate private property and wealth (Kuckertz, Berger and Mpeqa, 2016). Effective rule of law and PRs protect individuals in a fully functioning market economy. Secure PRs give entrepreneurs the confidence to undertake EA. Yoon, Kim, Buisson and Phillips (2018) use IEF to examine PRs amongst four other FIs as moderating variables with regards to innovation in nascent entrepreneurship in 47 countries from 2002-2012. Kuckertz et al. (2016) use IEF (including PRs) analysing data from 63 different countries with EA in factor-driven, efficiency-driven, and innovation-driven economies.

ATF relates to an efficient and accessible formal financial system (IEF, 2021). This ensures the availability of credit and investment services to individuals and businesses thus expanding financing opportunities and promoting EA. Such an environment encourages competition to provide the most efficient financial channel between investors and entrepreneurs (Boudreaux and Nikolaev, 2019). Raza et al. (2019) use ATF from the IEF when looking at entrepreneurial behaviours moderated by FIs for 51 countries over seven years (2001-2008).

The choice of the IEF is explained succinctly by Nikoleav et al. (2018) who commented that there are two main reasons for this:

i) Free market logic: Most studies examining EA in a NIT perspective use the free-market logic which is implicit in the concept of EF (Su et al., 2017). Free market economies reward effort and creativity with high social status. This encourages entrepreneurs to enter new markets generating profits through risk-taking and innovation (Nikolaev et al., 2018). Since OECD nations will have an opportunity motivated entrepreneurship (OME) element focus, this logic seems appropriate.

ii) Literature gap: The literature links EF to different entrepreneurial outcomes. Bjørnskov and Foss (2016: P.298) understand that much of this literature is still being discovered with previous articles having “…somewhat arrived at opposite conclusions”. This citation demonstrates that using IEF to examine TEA via an NIT lens may help address the gap.

Control variables:

Control variables are ones that are not the main interest to the researcher but are vital to properly understand the relationship between the independent and dependent variables (Allen, 2017). If these variables are not controlled, they can skew the results of a study (Allen, 2017). Nielsen and Raswant (2018) examine 246 articles from the top five International Business (IB) journals (2012-2015) to understand the implementation of control variables. They comment that researchers need to consider these variables of their effects to avoid a false positive (Type I) error. This is when a false conclusion arises that the dependent variable may have a causal relationship with the independent variables. Future studies may benefit from testing the extent to which controls act similarly across different institutional settings (Neilsen and Raswant, 2018). This thesis will attempt to examine this by emphasising the different informal institutional contexts within OECD countries.

The first control is economic development levels. Economic development is measured by GDP p/c divided by the mid-year population in this research (World Bank, 2021). Carree, Van Stel, Thurik, and Wennekers (2007) find that the level of economic development explains the number of entrepreneurs in each country. They also find that there is a ‘U-shaped’ curve relating EA to economic development. However, OME/necessity motivated entrepreneurship (NME) ratios may be more useful metrics, as opposed to GDP p/c, for understanding EA and economic development levels. Countries where entrepreneurship is motivated by perceived economic opportunity, usually have high-income levels. Amorós, Ciravegna, Mandakovic, and Stenholm (2019) understand that economic development is usually associated with higher opportunity costs of starting a venture because it entails higher formal registration processes (e.g., registration fees) and higher wages. The thesis follows Wennekers et al. (2007) and uses the OECD database for GDP p/c.

Additionally, a demographic variable the thesis controls for is age composition of 25-49 years old as a proportion of a country’s population. Brieger, Bäro, Criaco and Terjesen (2021) understand that when individuals go from mid-life to old age, they shift their value orientation from “instrumental” (e.g., financial security) to “terminal” values (e.g., social aims) (Kanfer and Ackerman, 2004). Blanchflower, Oswald and Stutzer (2001) comment that older people are more likely to be self-employed. However, younger people prefer being an entrepreneur. Prior research indicates that people in the middle-age demographics have the highest proportion of business ownership (Storey, 1994). In many countries, start-up rates of nascent entrepreneurship are highest in the age group between 25 and 34. This thesis uses the World Bank database for the ratio of 25-49 year-olds as a proportion of total population.

Next, female labour rates are understood as the proportion of female labour force (15-64 years old) divided by the total working-age population (OECD,2021). The literature has shown that males are more active in EA than females (Adachi and Hisada, 2017) and males attain better performance and create more jobs overall (Bosma, van Praag, Thurik and de Wit, 2004). Gender has a strong influence on EA as females tend to exhibit lower rates of entrepreneurial behaviour compared to males (Raza et al., 2019), although the difference varies across nations (Verheul, Stel and Thurik, 2006). The thesis will follow Wennekers et al. (2007) and use the OECD labour statistics.

Gross enrolment rates is the fourth control implemented in the thesis. Education participation rates is defined for both genders as number of students at a given level of education (irrespective of age) enrolled in primary, secondary and tertiary education as a percentage of the population (WB, 2021). Fuentelsaz et al. (2019) mention that the allocation of resources toward high-growth EA is positively related to education (Bowen and De Clercq , 2008). Hechavarría (2016) states that regardless of circumstances, entrepreneurs are highly educated and is fundamental. Simón-Moya et al. (2014) explain that studies demonstrate education helps identify opportunities in the marketplace, especially education in entrepreneurship (e.g., Levie and Autio, 2008; Shane, 2000). The author uses the World Bank database for gross enrolment education rates in the OECD nations annually.

Population density (P.Dens) is the last control. P.Dens is understood to be the people living in an area. This is usually measured as people per square kilometre within a country (UN, 2021). Wennekers et al. (2007) explain that that every area needs a minimum standard of infrastructure (e.g., facilities in retail trade). Therefore, less densely populated areas will have a sparse infrastructure. P.Dens is significantly related to the rate of EA for an economy (Reynolds et al., 1994). Meanwhile, urban areas will allow conditions of economies of scale through which smaller firms are disproportionately impacted (Bais, van der Hoeven and Verhoeven, 1995). Although, infrastructure and other supply side factors in urban areas (higher P.Dens) are beneficial to nascent EA in industries (Audretsch and Keilbach, 2004). This thesis uses data from the United Nations World Population Prospects Index for P.Dens as a control.

10) Model design, context and estimation:

The research question, the hypotheses and variables that the thesis will use have been stated previously. Now the estimations of the equation model itself will be examined. The thesis will utilise a multivariable regression analysis which will follow the general equation format of:

Y = βXn (*βYn) +ε

Where:

Y= Dependent variable (TEA)

βxn= Coefficient of the nth predictor of the independent variable (Informal institutions)

βYn = Coefficient of the nth predictor of the moderating independent variable (FIs)

ε= Error term (difference between the predicted and the observed value of Y for the nth observation)

The thesis examines two models:

i) TEA~ Informal institutions+ Control variables

ii) TEA ~ Informal institutions(* PRs) (* ATF) + Control variables

In this thesis, an unbalanced (where data is not collected annually) panel data is used examining TEA and its association with informal institutions (moderated by FIs) in 32 OECD countries from 2010-2020. A fixed-effects model will be used in the thesis. Fixed-effects models are a class of statistical models in which the values of the independent variables are assumed to be constant (Salkind, 2010). Only the dependent variable changes in response to the levels of independent variables (Salkind, 2010). A common research setting assumes a fixed-effects model where analysis is conducted under conditions present in similar studies. If the study is to be repeated, the same analysis levels of independent variables need to be used (Montgomery, 2001). Hence, results are valid only at the levels that are explicitly studied, and no extrapolation can be made to levels that are not explicitly investigated in the study.

Theoretical justification for using a fixed-effects model in the thesis may be proposed, the same justification used for data imputation. Nikoleav et al. (2018) explain that informal institutions are stable and take long periods of time before any incremental changes arise. This reinforces the point where a fixed-effect models is appropriate as the informal institution (main independent variable) values remain constant in the period examined

The thesis uses a forced entry regression method. This is where all the independent variables are forced simultaneously into the model (Field et al., 2012). This is adequate, as Williamson (2000) in Section 2 emphasises that informal institutions are seen as the foundation of institutions and economic action (and by proxy TEA).

The dependent variable (TEA) is a continuous variable. In this context, a continuous variable is one that can take on any value and is divisible (can be broken down into a non-integer whole number on the measurement scale being used) (Field, Miles and Field, 2012). The variable TEA can be broken into decimal percentages demonstrating this. For example, Austria has a raw TEA score of 6.2% for 2020 in the GEM database.

The Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) model is a technique of finding the unknown parameters in a linear regression model. The OLS model generates a line that best fits the data (finding a line that goes through as many of the data points as possible). This ‘line of best fit’ is found by determining which line results in the least amount of difference between the observed data points and the line itself, this model is generated by the statistical programme (Field et al., 2012).

An OLS model contains several assumptions including:

i) Normal distribution, ii) No correlation of independent variables with error terms and iii) Linear regression model (this assumption addresses the functional form of the model).

Looking at the dependent variable data point distribution (below), it can be noticed that a positive skew is present. This is where a higher number of data points have low values (Lawrence and Arthur, 2019). In the thesis’s context, TEA rates are low for OECD nations. Skewness tells the researcher about the direction of outliers. Figure 13 illustrates that a positive skew will mean most of the outliers are present on the left side of the distribution graph (Lawrence, 2019).

TEA percentage rates in OECD nations

Figure 7: TEA data distribution. Source: Author.

To correct for the positive skew and have a normal distribution for the dependent variable a logarithm (log) function can be used. The rationale for using a log function can help correct skewness (Benoit, 2011). Also, using log functions can help illustrate magnitude of effects as large percentage changes are displayed asymmetrically and can be corrected using the log function (Benoit, 2011). Using the log function allows for a more normal distribution.

Figure 8: Transformed dependent variable. Source: Author.

The interpretation of the results will be adjusted to the fact that a log transformation was used. In a non-transformed multivariable regression model, this would mean that an increase in 1 unit of the independent (X) variable would result in a change of the magnitude of x units (coefficient of X variable) of TEA. For example, if the PD coefficient is 0.4, then a 1% increase in PD will result in a change of 0.4% in TEA.

With a log transformation, the underlying model is:

Ln(Y) = βXn (*βYn) + ε.

This can be expressed as Y=exp (βXn (*βYn) + ε). Therefore, the relationship between Y and X variable is not additive with a log form. When the dependent or independent variable is log-transformed, the interpretation of the coefficient is exponentiated, subtract 1 from this number, and multiply by 100. This gives the percentage increase (or decrease) for the dependent variable for every 1-unit increase in the independent variable. For example, if the PD coefficient is 0.198. then the interpretation would be: (exp(0.198) – 1) * 100 = 21.9%. For every 1-unit increase in PD, TEA increases by about 22%.

11) Results (answering the research question):

For Model 1, half of the hypotheses are supported (IND, UA and IVR). Moreover, informal institutions moderated by formal institutions (Model 2) overall generate inconsistent results. As a highlight, five of the six PR-moderated hypotheses generate a significant positive moderating influence on the association between informal institutions and TEA. Informal institutions represent the attitudes of potential entrepreneurs. The hypotheses here appear to suggest that such attitudes only lead to new ventures when supported by effective PRs. Indeed, these hypotheses appear to correspond with Bylund and Mcaffrey’s (2017) theory (see Section 2), where informal institutions are considered the foundation (push factors) and FIs the support (pull factors) of TEA. This suggests that the quality of PRs institutions might influence new venture formation and development. Once nascent entrepreneurs learn about how to navigate the PRs they engage with, rates of TEA may increase (Estrin et al., 2013). Without effective PRs, an entrepreneur’s desired future state becomes risky (Baumol, 1990) as a lack of such PRs reduces protection for acquired assets and therefore incentives to explore possible opportunities, this may result in lower rates. A negative PRs moderation effect is noted for the MAS dimension and its association with TEA. This may arise because active competition is consistent with high MAS, and entrepreneurs are better able to improve their economic situation by seizing initiatives, not needing support from PRs (Graafland and de Jong, 2021). Effective PRs may protect producers from entrepreneurs who may be comfortable with obtaining material gains at the expense of other entrepreneurs (Park, Russell and Lee, 2007). It is these protections that may deter prospective entrepreneurs from engaging in nascent EA as their PRs may be exploited by established entrepreneurs.

However, only one of the six ATF-moderated hypotheses is positive and significant (MAS dimension), and ATF has a significant negatively moderating influence on the other informal institutions and TEA. ATF may have a negative moderating effect on informal institutions’ associations with TEA, as at lower-quality institutional settings, human and financial institutions may have a larger explanatory power in influencing TEA (Boudreaux and Nikolaev, 2019). Thus, possessing easier ATF resources is positively associated with OME when there is a lower-quality institutional environment present (like the OECD nations). This may then have a weaker association as a moderator of the association between informal institutions and TEA (Boudreaux and Nikolaev, 2019). However, the emergence of modern sources of finance may have allowed talented entrepreneurs to obtain funds from alternative sources and not just traditional financial institutions.

Interestingly, the MAS dimension was the only cultural dimension where effective PRs had a negative moderating effect on its association with TEA. Looking at the direct association between MAS and TEA, entrepreneurs may be associated with high MAS (Abbasi et al., 2021). Therefore, in high MAS countries, a greater acceptance of challenges may be realised, suggesting that entrepreneurs may be more likely to innovate and may positively engage with TEA (Tian et al., 2018). Having easier ATF might therefore allow nascent entrepreneurs to realise their potential, stimulating TEA. Entrepreneurs in high MAS cultures have greater trust in their ventures and may therefore allocate additional resources to achieve success, independence, and recognition at the expense of lower profits compared to entrepreneurs in low MAS cultures (Shao et al., 2010).

12) Limitations and future direction of research:

The thesis has several limitations:

i) Types of entrepreneurship examined: This thesis has examined only the opportunity-motivated (OME) component of TEA, due to the country sample of rich OECD nations examined in this thesis. Many studies look at both OME and necessity-motivated (NME) components separately as it is acknowledged that NME also has high levels occurring within OECD nations (e.g., Germany has a ratio of 2:1 ratio for OME to NME for all its TEA).

A criticism of TEA can also be seen in its composition: TEA examines the percentage of 18–64 year olds engaged in TEA that has taken place for at least 42 months (Reynolds et al., 2002). This age range is wide for this measure, and the thesis has already implemented age as a control variable. Therefore, a criticism of the TEA measure are the facts that older people are more likely to be self-employed (Blanchflower et al., 2001) and middle-aged people have the highest proportion of TEA (Storey, 1994). Research generally appears to indicate that middle-aged people have the highest proportion of business ownership (Storey, 1994), and therefore, an ageing population in most developed countries may imply a threat to the future development of EA (Wennekers et al., 2007).

ii) Updated Hofstede’s values: Stability appears present within national cultural dimensions, but this stability has apparently decreased over time. Chun, Zhang, Cohen, Florea and Genc (2021) explain that there is a great deal of literature indicating value changes in a society’s culture (e.g., Inglehart, 1997; Inglehart and Baker, 2000). Globalisation may bring changes in certain Hofstede dimensions (e.g., possibly higher IND and lower PD). Further evidence of cultural changes over time is evidenced by Taras et al. (2012) who examined 451 published empirical studies with data from 49 countries and regions. Focusing on the use of meta-analysis in cultural studies research and the perseverance of Hofstede’s dimensional characteristics, the authors find strong suggestions of diminishing correlations of recent values with Hofstede’s original results over time.

iii) FIs : Whilst this thesis looks at the FIs of PRs and ATF, other studies have used a variety of FIs. For example, Fuentelsaz et al. (2019) assess the influence of formal institutions (moderated by informal institutions) and OME looking at 84 countries (2002-2015), including voice, accountability and political stability amongst other formal institutions. Nikolaev et al. (2018) examine OME and NME in 73 countries (2001-2015) using 44 variables on institutions including corruption, fiscal freedom, religion and legal system origin. Using additional variables may allow for a more comprehensive understanding of how TEA is influenced by different forms of FI. Since OECD nations generally have a high-quality institutional environment, weak effects of financial capital moderation on OME may be seen (Boudreaux and Nikolaev, 2019). Therefore, exclusion of ATF from future studies may be reasonable.

iv) Country sample: This thesis examines 32 OECD countries, yet other papers examine a wider range of countries. Several other studies examine a much wider country coverage, e.g. Junaid et al. (2022) analyse 74 from Africa, Asia, Europe and South America (S.America). Fuentelsaz et al. (2021) note 74 countries from Africa, Asia, Europe, S.America, North America. Additionally, Nikolaev et al. (2018) study 73 countries comprising countries in Asia, Europe, S.America, Africa and Oceania. Having a wider country coverage may facilitate a more generalised understanding of the influences of institutions (formal and informal) on TEA globally as opposed to OECD countries only.

v) Regional differences/disparities: This issue was referred to in Section 7 as the reason for omitting certain L.A. countries. By conducting cross-country TEA studies, the mechanics of how various institutions and their associations with TEA are better understood, regional differences within each country however are not examined in such settings. Stenholm, Acs and Wuebker (2013) indicate that extensive research has identified important differences in the rate and type of TEA within nations at a regional level, with discrepancies between regions linked to knowledge spillovers and the amount and quality of entrepreneurial talent impacting regional TEA performance (Audretsch, Bönte and Keilbach, 2008). Stenholm et al. (2013: P.190) mention that this “…will help to illuminate how different institutional arrangements influence both the rate and type of entrepreneurial activity in a region. Future work could explore the role of institutional “micro-climates” that help to promote and foster…growth within a country, helping to explain within-country variance”. This citation points to the fact that understanding regional TEA (which makes up national TEA) allows for a greater awareness of the mechanics and interactions of institutions with TEA. It may be beneficial for researchers to examine regional disparities within a particular country and the differences in TEA rates within the country as opposed to cross-country studies.

Reflecting these limitations, there are many future research areas that could be further explored:

i) Exclusion of LTO: As pointed out in Section 3, a claimed contribution is addressing the theoretical gap by studying LTO’s (main and moderated) association with TEA where only one of three hypotheses appeared to be supported. This thesis questions the validity of examining LTO in future studies of a similar nature. Theoretical ambiguity exists in relation to LTO’s association with TEA. Lumpkin et al. (2010) comment that TEA in rapidly evolving situations require decision makers to change long-term priorities which may impact TEA. Barretto et al. (2022) conclude that LTO has an initial significant effect on implementing TEA but the mindset of perseverance in high LTO contexts may be detrimental to TEA. A major issue with the LTO dimension, asides from the gestation periods differing by industry, is also the fact that there will be various projects with different time horizons within a specific industry. For example, two different projects may occur in the mobile phone industry with two different ventures. One project may be a particular component being upgraded on phones (e.g., software upgrade) versus having a new phone model created altogether. Greater LTO will favour the latter (long-term project) but not the former (short-term project), hence, it may be difficult to theorise the overall association between LTO and TEA, since both ventures will count as TEA, and to explain the empirical results since the time horizons of projects contributing to TEA will be unknown. Potential exclusion of the LTO dimension may therefore be sensible for future studies.

ii) Alternative national culture indices: A point emphasised in the literature when examining national culture indices is the fact that Hofstede’s indices are assumed to be stable and are not responsive to changes globally or within society. Amongst other issues with Hofstede’s index, researchers have therefore suggested utilising alternative indices (e.g., GLOBE and Schwartz). Indeed, Taras et al. (2012) explain that an alternative to Hofstede’s index may be a meta-analysis (combining multiple indices) of the various dimensions in different indices, as this may be better suited for handling the sampling uses across time periods and specific populations of interest as post-Hofstede research advanced the understanding of culture yet was subject to the same limitations that Hofstede has (i.e. the lack of data generalizability across population and time). Examining the same population (countries) at different times may offer better insights into the implications of national cultural dimensions via a longitudinal perspective.

iii) Focus on NME and emerging markets: This thesis focuses on OECD nations and TEA where focus is on OME. Emerging countries, e.g., ‘BRIC’ nations (Brazil, Russia, India and China), are of interest due to their potential in terms of economic significance, being some of the world’s largest economies (e.g., China being the second largest economy by GDP) (World Bank, 2022). Buccieri, Javalgi and Jancenelle (2021) examine dynamic capabilities in SMEs from emerging countries and mention that they account for more than 50% of employment and contribute approximately 50% of GDP in emerging markets (Alibhai, Bell and Connor, 2017). In these nations, despite a growing amount of OME, NME will still be a significant proportion of TEA. Since they are a relevant group in developing countries (Rosa, Kodithuwakku, and Balunywa, 2006), further studies of NME will allow a better understanding of TEA in emerging markets.

iv) Level of analysis: The website earlier addressed ambiguous LTO results; the gestation period (referring to the ‘clock speed’ theory) was discussed and how this will vary by industry. It was further suggested that since TEA was an aggregate national level measure for all industries. An issue with such cross-country studies examining TEA, therefore, is that policy makers and academics are given a general picture, but specific policies and a better understanding of specific industries are missing. Having a specific industry focus (within a country or a group of countries) could allow more informed decision making, but this would require entrepreneurship activity data by industry. For example, Choi, Ha and Kim (2021) note S. Korean SME patent and utility model data from 77 ventures (with a combined 912 venture years in total) from 2000 to 2017 in the S. Korean electronic parts industry when examining innovation associations. Such a citation demonstrates that an industry focus may be beneficial for understanding specific industries and their associations with national cultural dimensions rather than cross-country studies.

v) Feasible generalised least squares (FGLS) regression model: Section 10 explains the features of an OLS model and its limitations. The FGLS coefficients of a linear regression are a generalization of the OLS model. FGLS is essentially used to deal with situations in which the OLS coefficients are not ‘BLUE’ (best linear unbiased estimators) (Kariya and Karuta, 2004). Fuentelsaz et al. (2021) examine entrepreneurial exit from an institutional perspective and consider high-growth aspiration initiatives amongst panel data for 74 countries from 2007-2017. In the study, they recommend using a FGLS model, thus a model corrects for issues of heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation which can be common for panel data (Anokhin and Schulze, 2009; Audretsch and Thurik, 2001). Choi et al. (2021) also use a FGLS model when noting S. Korean SME patent and utility model data from 77 ventures (covering 912 venture years) from 2000 to 2017 in the S. Korean electronic parts industry and innovation associations. Choi et al. (2021: P.15) observe that “…OLS estimation might yield biased estimates due to unobservable heterogeneity in firm characteristics. We therefore adopted panel-data linear models using FGLS, which is known to provide more reliable estimates in the presence of heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation”. Both the articles examined here illustrate that FGLS is a contemporary model being explored in the entrepreneurship literature. Using such a model may generate some useful insights, correcting for OLS issues.

13) Ending note:

Entrepreneurs face vast uncertainty when establishing ventures, so unprecedented support from FIs was witnessed globally (e.g., furlough employment protection schemes and quantitative easing via lowering interest rates) during the first Covid lockdown. This prompted the author to wonder about the connections between FIs and how people within a country would interact with this FI support regarding entrepreneurship generally. From this and with support from academic staff within the University, the topic of NIT and TEA emerged. The national focus of this thesis was necessitated by the Covid crisis, i.e. it was written, conducted and written up during the first two years of the Covid-19 pandemic, despite all the uncertainties surrounding lockdown and anticipation of life returning back to normal. This meant that the author had to assess feasibility issues and adopting a NIT study examining secondary data at a macro level was the most appropriate route, given its prominence in the literature and. This allowed the author to finish writing-up on time despite the global uncertainties from 2020 onwards.